Holly Krieger is Professor of Mathematics at the Department of Pure Mathematics and Mathematical Statistics (DPMMS). With over 11 million views for her appearances on Numberphile, she has also connected with a wide audience to share the beauty of the subject. She talked to us about her research, mathematical communication, and interesting advice for people starting out on a career in maths.

Krieger works in the overlap of two areas of mathematics: number theory and complex dynamics. Her reason for choosing this intersection, which is known as arithmetic dynamics, wasn't entirely down to the mathematics. "What I liked most about [this area] were the people who work in [it]," she says. The field was founded around thirty years ago by the mathematician Joseph Silverman and many of the researchers who work in it are relatively young. "It comes down to a small handful of people, who are the leaders in the field, [being] very pleasant to talk mathematics to and very nice to work with."

Number theory

On the mathematical side Krieger was drawn by the age-old lure of number theory, which studies the fundamental constituents of mathematics. "I assume that every person who goes into physics at first wants to understand the Universe — they want to understand [its] building blocks." The building blocks of mathematics are (arguably) numbers. As Carl Friedrich Gauss is said to have claimed, "Mathematics is the queen of the sciences and number theory is the queen of mathematics."

Another tantalising aspect of the area is that questions are often very easy to state, yet fiendishly difficult to prove. An example is Fermat's Last Theorem which says that there are no integer triples x, y, and z, which satisfy the equation

xn+yn=zn,

when n is an integer greater than 2. In 1637 the mathematician Pierre de Fermat wrote into the margin of his textbook that he had found a "marvellous proof" for this fact, which the margin was too narrow to contain. The scribble taunted mathematicians for over 350 years, until Andrew Wiles announced a proof at Isaac Newton Institute here in Cambridge in 1993. The proof helped to develop a whole new area of mathematics, which now occupies various members of the Mathematics Faculty here in Cambridge (you can find out more in this article.)

"Fermat's Last Theorem catches people's interest because it seems so fundamental," says Krieger. "Number theory is an easy sell because the questions are fundamental, but they have been studied for so long that there's a lot of mathematical depth there and a lot to learn."

Complex dynamics

Complex dynamics is an entirely different area of study, at least at first sight. Very loosely speaking, it involves points moving around on the two-dimensional plane according to a rule given by a mathematical function. This creates a dynamical system. (Technically, the dynamical systems come from iterating a functions of a complex variable.) These dynamical systems are a far cry from those we observe in real life — such as the weather or the motion of the planets — but the mathematical insight we can gain from the purely mathematical view can shed light onto real-world phenomena, such as chaos.

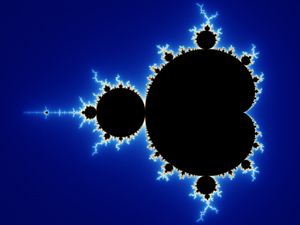

Complex dynamical systems give rise to beautiful fractals that have made a name for themselves even outside of mathematics. Examples are the famous Mandelbrot set and other fractals known as Julia sets.

The Mandelbrot set. Image by Wolfgang Beyer.

"Complex dynamics became interesting to me in part because I started interacting with people who are interested in it," says Krieger. "But also, there's an appeal to the field because it has a flavour of experimentation. Even though it's an area of pure mathematics, you can draw these wonderful pictures and make predictions about what you think is happening mathematically. [The field] is motivated by that kind of experimentation in a way that [other parts of pure mathematics] are not."

Secret dynamics

Number theory and complex dynamics appear as disparate areas, but as Krieger points out, many number theoretical problems are secretly dynamical. She alludes to the famous Fibonacci sequence, in which each number is the sum of the two previous ones. Starting with 0 and 1, the process of adding gives

0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, …

Despite the sequence's fame and long history (it was known to Indian mathematicians as early as 200BC) there are still things we do not know about it. It is not known, for example, whether there are infinitely Fibonacci numbers that are also prime numbers. But as Krieger points out, the process of generating the Fibonacci sequence is a dynamic one. And it turns out that you can translate it cleanly into the context of complex dynamics (by thinking of two preceding numbers as a vector, which is associated with a point in the plane). This gives you new tools for investigation.

There are also other examples of concepts that are familiar from number theory but have a dynamical interpretation. "And once you have that interpretation you can either [try to] generalise what you know about [them] to other dynamical systems, or you can [ask] whether the dynamical tools can tell you anything that the number theoretical tools couldn't."

In her work Krieger has been exploiting the fruitful overlap of number theory and complex dynamics to great success. In 2020 she won a prestigious Whitehead Prize from the London Mathematical Society. In 2023 this was followed by an equally prestigious Leverhulme Prize. You can find out a little more about her work in this article.

Enjoy maths, enjoy life — and keep working

Krieger enjoys her life as a mathematician, not just because of the interesting mathematics. "[It's] a very good career to be a human person in," she says. Contrary to popular belief, research mathematics is not all about being shut up alone in an office. It can offer opportunities for travel and flexibility to create a balance between work and life.

Krieger's advice to people thinking about a career in mathematics is to keep in mind the social side. "Think about who you will work with, [not just about the area you will work in]. The people you work with are just so critical."

When it comes to the part of mathematics that does involve sitting on your own and thinking deeply, Krieger's advice is to persevere, even in the face of adversity. "When you are stuck, keep working," she says. "It is intellectually difficult to get far in mathematics, everyone is going to get stuck at some point. One thing you really want to avoid is getting circularly stuck: not only are you stuck but you're beating yourself up for being stuck, so you're going round and round a circle of negative thoughts. What you can do is say, 'ok, this is hard, but I am going to carry on anyway'."

As Krieger herself has proved, it's also possible to have fun with high-level mathematics outside of academia. In her appearances on the YouTube channel Numberphile she has shared the beauty of maths with a much wider audience, exploring a range of topics — including, for example, how the Fibonacci sequence appears in the Madelbrot set.

"Without being too philosophical, the point of life is to communicate with other humans," she says. "It's just so valuable to be able to establish that little thread of communication with so many people. [When I first started doing Numberphile], I didn't recognise that there is such an appetite for [talking] to expert mathematicians. That was a surprise to me and I'm really grateful for it — it was a happy surprise!"

Ten years and counting

Next year Krieger will celebrate ten years of working at DPMMS. "It's basically the best job a mathematician can have," she says, due to the calibre of her colleagues and the mathematical depth of the research that happens here. It's an intense environment, but she finds the challenge inspiring.

"The shocking thing is the students," she says. "Comparing my 20-year-old self with these students, I'm just so impressed with how mathematically mature they are and how focussed they are on what they are doing. To teach someone who really cares and wants to learn what you have to teach them — you can't beat that!"