In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Winton Centre for Risk and Evidence Communication, based at the Department of Pure Mathematics and Mathematical Statistics (DPMMS), has been investigating a crucial aspect of the crisis: people's perception of the risk the disease poses and their attitudes to governments' responses.

These attitudes are crucial. The severe social interventions now in place will only be successful if people stick to them. Whether they do depends, at least in part, on how seriously they take the threat posed by COVID-19 —and this depends on how well governments communicate the science and mathematics behind it.

Issues such as these lie firmly within the remit of the Winton Centre. "We are interested in how best to communicate scientific evidence, and how different ways of doing that affects people's understanding, worry, and ability to make decisions," says Alexandra Freeman, Executive Director of the Centre. The multi-disciplinary team at the Centre works with agencies and individuals that need to communicate quantitative evidence in a balanced, impartial way, but it also works to empower audiences to be able to critique the numbers they are being told. This multi-faceted aim requires cross-disciplinary efforts, drawing not only on the expertise of statisticians and scientists, but also on that of journalists and psychologists.

Perhaps the most striking thing is the similarities across countries, but there are also some subtle differences hidden in there. Alexandra Freeman

A recent Winton Centre study, published rather fittingly on the day the UK prime minister announced a lock-down, addressed an important question when it comes to communicating complex scientific issues: how should one deal with the fact that scientific evidence often comes with uncertainties. This is particularly pertinent at the moment, as there is still a lot scientists don't know about COVID-19 and the way that social interventions, might affect the spread of the disease (see the feature article Fighting COVID-19). The big question is whether being told about the uncertainty surrounding a particular issue might cause people to lose trust, not only in the facts and numbers they are being told about, but also in the sources these come from.

The results of the study were reassuring: they suggest that being told about uncertainty only causes a small decrease in trust in numbers and trustworthiness of the source — and when it was done as precisely as possible, with a numerical range, this change was negligible. As part of their COVID-19 work, the Winton team have repeated the same experiment using uncertainty around the mortality rate from the virus and confirmed the results even in this very present, emotional context. This should help reassure communicators, including those who are currently informing us about the COVID-19 pandemic, that they can be open and transparent about the limits to what they currently know.

Attitudes to the COVID-19 crisis

The latest Winton Centre study concerning attitudes to the COVID-19 crisis builds on the Centre's work on uncertainty. Around the end of the third week of March the Centre collected data from people in seven countries: the UK, US, Italy, Spain, Germany, Mexico and Australia. The aim was to find out what people think and feel about this unprecedented situation, the severe limitations imposed on their freedoms, and the way their governments are dealing with the crisis and keeping them informed.

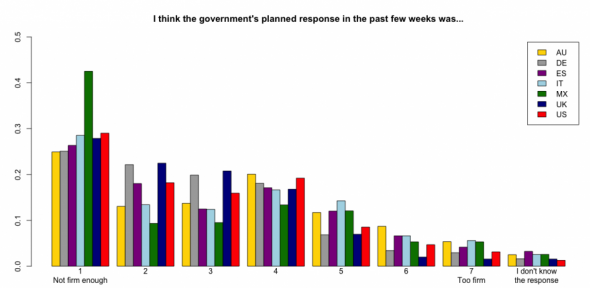

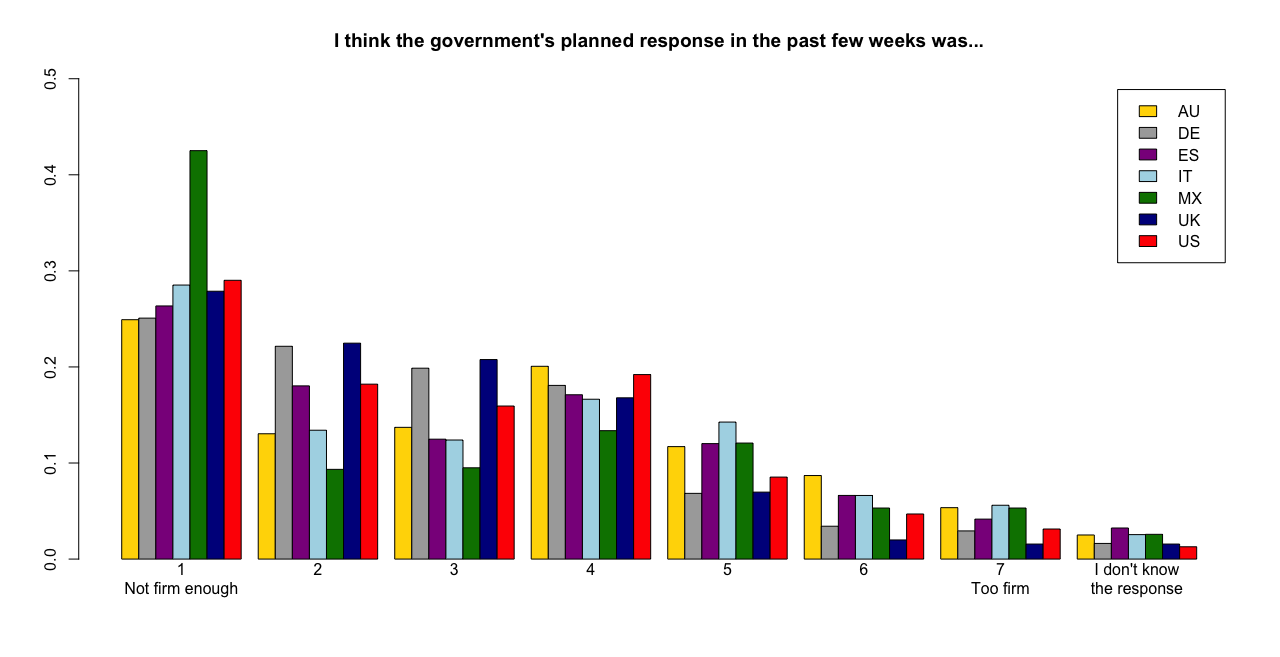

The initial analysis of the results gives a first glimpse of the attitudes and make fascinating reading. "Perhaps the most striking thing is the similarity across countries (with Mexico as the most different)," writes Freeman on the Centre's blog. Worry about the virus is high in all countries, but perhaps surprisingly, people from all countries felt their governments' response in the past few weeks had "not been firm enough". Even Italians, who had been living with strict social distancing measures for at least ten days before the survey and Spaniards, who had been under lock-down for a week, felt this way. "Mexico, with the fewest restrictions at the moment, is most united that the response is definitely 'not firm enough'."

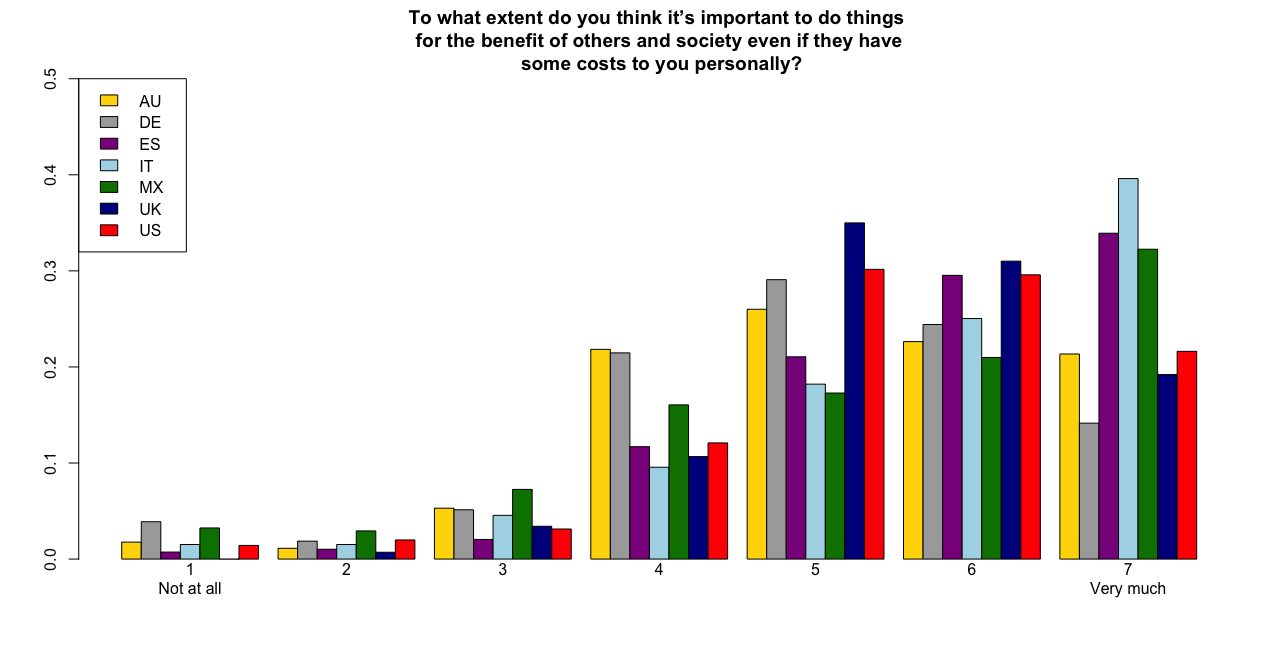

But there were also interesting differences "One thing that we thought might affect people's attitude to their government's strategy was how much they felt that we as individuals should give things up for the benefit of society, and here the cultural differences are, perhaps, surprising," writes Freeman. "Italy seems incredibly pro-social whilst Germany — and the UK — much more individualistic."

Variation was also found in the level of trust people in different countries have in their government to deal with the crisis. Germans are leading the way here, with levels of trust much higher than in Mexico, the UK and the US.

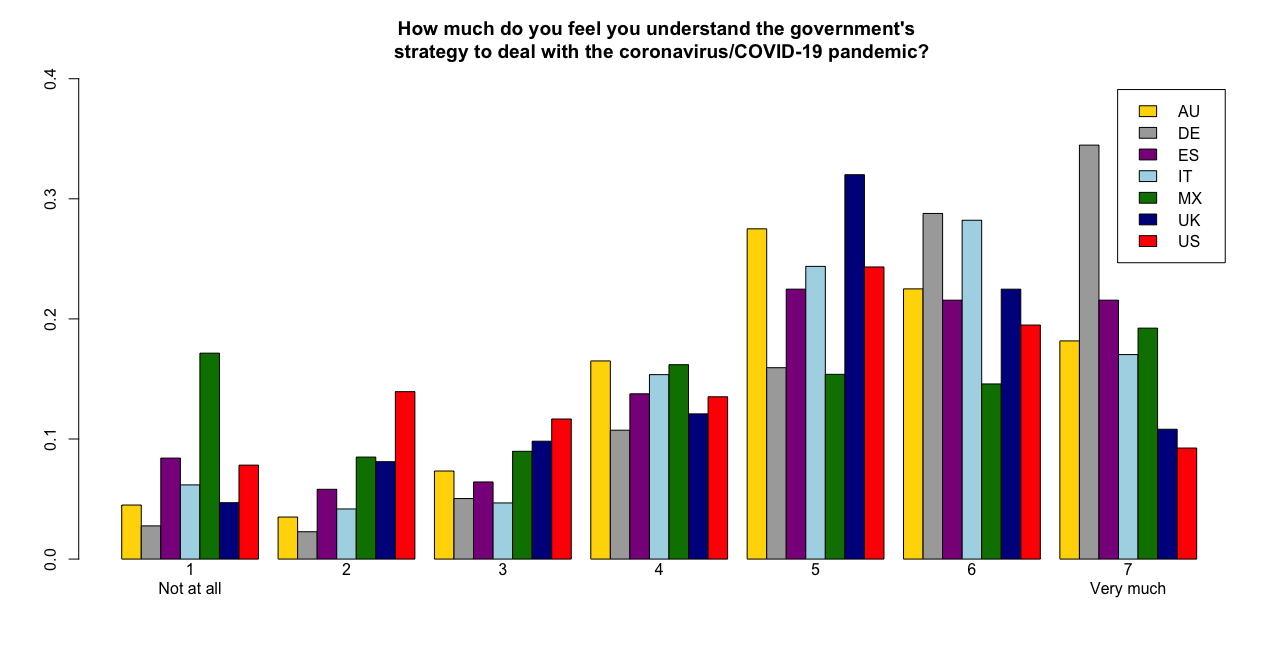

This may partly be down to how much people feel they understand their governments' strategies, which may in part depend on how well they feel they understand the science and mathematics that informs them. Here there is again a lot of variation. "Germany seems particularly confident about their understanding of the government's strategy, whilst the UK and US much less so," says Freeman. (This data was collected before the UK prime minister's broadcast on the 23rd March which started a lock-down).

Trust in scientific advisors, however, was high in all countries.

The initial summary of the findings, shown in more detail on the Winton Centre blog, is only the tip of the ice berg. Over the next few weeks the Winton Centre will be subjecting the statistics to a more extensive analysis. They are running their survey in more countries, and are planning to survey the UK several times over the next few months. The results will not only be interesting for policy makers and communicators during the current crisis, but hopefully also inform the way they will communicate with us in the future.

In the meantime, governments and their officials might be well advised to heed the advice of David Spiegelhalter, Chair of the Winton Centre, on communicating during a crisis.

"You should be communicating a lot, consistently and with trusted sources," he says. "You have to be open and transparent. You have to say what you do know and then you have to say what you don't know. You have to emphasise, and keep emphasising, the uncertainty, the fact that there is much we don't know. Then you have to say what you are planning to do and why."

"Finally, you have to say what people themselves can do, how they should act. The crucial thing to say is that this will change as we learn more."

If there is anything positive about this pandemic then it's perhaps the fact that we are all getting to witness science in action. This may influence our future attitudes to the uncertainties involved and make the job of communicators a little easier. Whatever the impact on public attitudes, the work of the Winton Centre will help inform policy in the future.

Find out more about the work of the Winton Centre related to the COVID-19 pandemic on the Centre's website.